Latest News

A Vital IBM Technology Helps Nonprofits Prepare for Disaster Season

By Trish Hall Jil Christensen, a pianist who composes experimental electronic music, has always been resourceful. She put herself through Bard College, at one point sleeping in a tent because it...

By Trish Hall

Jil Christensen, a pianist who composes experimental electronic music, has always been resourceful. She put herself through Bard College, at one point sleeping in a tent because it was all she could afford.

Until two years ago, though, she had never jumped into relief efforts during hurricanes, or been part of an organized nonprofit.

Nevertheless, when Hurricane Florence struck in 2018, Christensen (below), who lives in Durham, N.C., started a new organization on the spot: using pilots to deliver supplies to people in need. She started with friends who had pilot licenses, and they in turn pulled in friends who were also eager to help.

Her organization, Day One Disaster Relief, goes wherever the gaps are, and recently that has been the supply chain for the COVID-19 response. Her group has secured and delivered gowns, booties and masks to federal prisons, emergency departments in hospitals, farmworker camps—wherever the need was greatest.

Her organization, Day One Disaster Relief, goes wherever the gaps are, and recently that has been the supply chain for the COVID-19 response. Her group has secured and delivered gowns, booties and masks to federal prisons, emergency departments in hospitals, farmworker camps—wherever the need was greatest.

Christensen’s toughest challenge, however, might be coming up. COVID-19 is surging in the South. And this year’s hurricane season, which started in June and continues through November, is predicted to be harsher than usual. How do you not only keep people safe after their homes have been destroyed, but also keep them socially distant? And how do you keep your volunteers safe when they enter coronavirus hotspots?

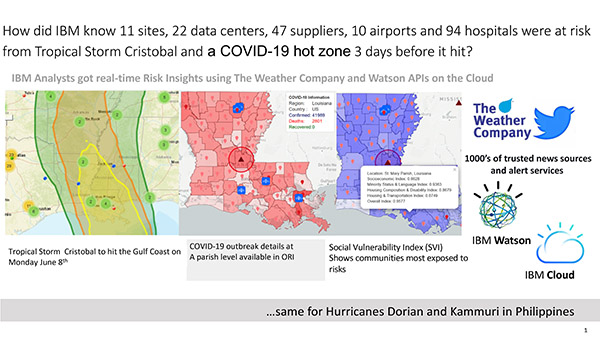

IBM has made Christensen’s tough job immeasurably easier. It has provided her and other nonprofits free access to a technology platform called Operations Risk Insights (ORI). The platform frees her from the necessity to scan hundreds of local weather reports and to keep track of hospitals and warehouses.

With ORI, everything is in one place, constantly updating, so that decisions can be made faster and smarter. Other disaster relief groups using ORI include Good360, LIFT Non Profit Logistics, Save the Children, Information Technology Disaster Resource Center (ITDRC) and American Logistics Aid Network (ALAN). Organizations can customize ORI to better understand their respective geographical regions by tracking weather patterns, COVID-19 cases and locations of the poorest, most vulnerable people, as well as sites of hospitals, airports, private airstrips and warehouses.

In the next few months, especially if COVID-19 continues its relentless spread, ORI could prove vital in saving lives as hurricanes begin to pound the coasts. “Instead of having to call and get all these status updates, I have this incredible platform that alerts me so I don’t have to do as much digging and I can maybe get a little sleep before I start responding,” said Christensen, who focuses on delivering supplies and food.

IBM ORI With Watson

The ORI technology was developed by a team led by Tom Ward (below), who joined IBM more than 30 years ago, shortly after he graduated from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He is a supply chain and big-data specialist whose job is to apply AI and cloud technologies to solve business problems for IBM’s internal operations.

Ward and his team started working on ORI five years ago to help IBM minimize disruptions to its supply chain. The inspiration had come in 2011, when a tsunami in Japan, floods in Thailand and a volcano in Iceland created worldwide chaos for businesses.

“We scrambled,’’ Ward recalled. “We had people flying parts that were needed all around the world. We decided we had to be smarter and that there had to be some way to use cloud and AI technologies.”

“We scrambled,’’ Ward recalled. “We had people flying parts that were needed all around the world. We decided we had to be smarter and that there had to be some way to use cloud and AI technologies.”

With ORI, if there is a major weather disruption forecast, IBM can immediately seek alternate plans. “It’s all about speed,’’ Ward said. “We need to outrun our competitors.”

Since IBM started using ORI internally in 2016, he estimates it has saved the company $15 million. In early 2019, the company began offering the platform to nonprofits, and later that year released it as a commercial offering.

While Ward said he is proud of creating a service for IBM to improve operations, “what excites me more is helping people like Jil who are trying to help the most vulnerable.”

Ward has close relationships with the nonprofits, and continually adapts and updates the platform to meet their needs. In one change they requested, ORI now provides population density information as well as the locations of counties considered the most “socially vulnerable” due to poverty, a lack of transportation and crowded housing. The newest addition will bring in related posts from social media sources, so that rescuers can see where a particular family might be stranded. With the changes in the ORI platform that should come by the end of this quarter, Christensen and other users will no longer have to scan social media, but will be able to use the platform to see hashtags that can be informative. Another enhancement will allow users to turn the various layers of data on and off so they can be viewed on maps in the combinations needed at that moment.

Because of the platform, nonprofits don’t have to go on a variety of different websites to find what they need when time is short. They can make decisions quickly and arrive in threatened areas before the storms hit. The platform pulls together information from The Weather Company, real-time flood and drought data from the National Weather Service and earthquake disaster data from the U.S. Geological Services and the Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System, as well as up-to-the-hour news reports and social media posts.

Finding the True Hot Spots

The quick access to layers of data lets nonprofits focus on the most desperate people. Before Hurricane Dorian, IBM models accurately predicted it would hit much further north than other forecasts, which were expecting the worst areas to be around Miami. Because agencies planned to help people in Florida, North Carolina was badly exposed. IBM data allowed Christensen (left) to find the hot spots, call community partners and create logistics plans.

“Jil wants to land those planes where the most vulnerable people are,” Ward said. “She doesn’t need to take supplies to Hilton Head,” he said, referring to an affluent community. People with money tend to evacuate before storms, but people who can’t afford to leave hunker down and hope.

Christensen, still a professional musician, never pictured herself working in disaster relief. But she sees similarities between her two vocations. Like disaster relief, music “takes a lot of non-linear thinking,” she said. “I see pieces in my head as a three-dimensional object, and I put them into linear time.’’

Disaster relief, she said, “is literally like composing.” When Florence hit, she rallied all of her pilot friends, and they pulled in their friends, and eventually 555 flights with supplies were made to areas that weren’t otherwise getting help.

She is the sole employee of her organization, having begun taking a salary only last month. But by using the IBM technology as a force multiplier, she can rally her 2,000 volunteers and many local community groups to nimbly help people before the big organizations like the Red Cross arrive.

“We trust that the community leaders or churches know their community,’’ Christensen said. “We come in, we become their disaster relief. They become distribution. They stay in control. They decide when they are done.”

Christensen is very aware of the double risk factors coming up, for both poor people and her volunteers. “My biggest fear right now is running into communities that don’t take COVID seriously,” she said.

But it’s worth it to her, in part for the positive collaboration with IBM and all she has learned about data, and in part because she found something that is truly needed.

“If you find something that impacts lives,” she said, “don’t stop doing it.”