IBM and Coronavirus stories

Sharing patents to fight COVID-19, IBM taps a broad research portfolio

By Diane Cardwell

A sugar-enhanced molecule that might keep viral infections at bay. Algorithms that can help predict the scope of an epidemic. And here’s something that may become increasingly relevant as people spend more time connected through devices: a touchscreen that can sterilize itself.

These are but a few of the innovations that could grow from IBM’s vast trove of patents—among the largest such portfolios in the world. The company has pledged to let anyone working on solutions to the coronavirus pandemic use its patents for free. More than 80,000 valuable IBM patents and patent applications can now support researchers everywhere who are developing technologies to help prevent, diagnose, treat or contain COVID-19.

The collection includes thousands of IBM artificial intelligence patents, some related to Watson technology, as well as dozens, if not hundreds, related to biological viruses.

“What this does is help anyone on the front lines of fighting against the pandemic not worry about infringing on any of our patent portfolio,” Manny W. Schecter (left), chief patent counsel for intellectual property law at IBM, said of the agreement, which will also cover patents granted from new patent applications filed through the end of 2023.

The move will not only let researchers avoid paying licensing fees for innovations that derive from the patents, Schecter said, but will also allow them to avoid the time and effort of navigating the licensing process. “They’re not distracted even worrying about this when working on important activities related to combatting the virus.”

Tech Titans Battling a Common Foe

The IBM commitment is part of a broader program, known as the Open COVID Pledge, that has attracted an extraordinary level of buy-in from big technology players—companies that are often fierce competitors but are now cooperating to tackle a global problem of unprecedented magnitude.

“The response to this immediate pledge has been overwhelming,” said Diane Peters, general counsel and corporate secretary of Creative Commons. Her group, which helped organize the pledge, is a nonprofit organization dedicated to making it easier for people and organizations to share intellectual property.

The positive response from the tech giants, she said, is inspiring smaller companies holding rights to less, though relevant, intellectual property to come forward as well.

“This is the private market ordering itself to figure out a solution,” Peters said. “My hope is that companies learn how to share IP in a way that is beneficial to society.”

John E. Kelly III, IBM's executive vice president, who oversees the company's intellectual property strategy, said participating in the pledge was in keeping with the company's commitment to inventions that make a difference.

“Innovations driven by IBM have helped to power our industry, and the industries of our clients," Kelly said. "For decades, we've brought innovation that matters to the world, and this is a critical time when the world can benefit from the leading-edge thoughts of IBM's researchers and inventors."

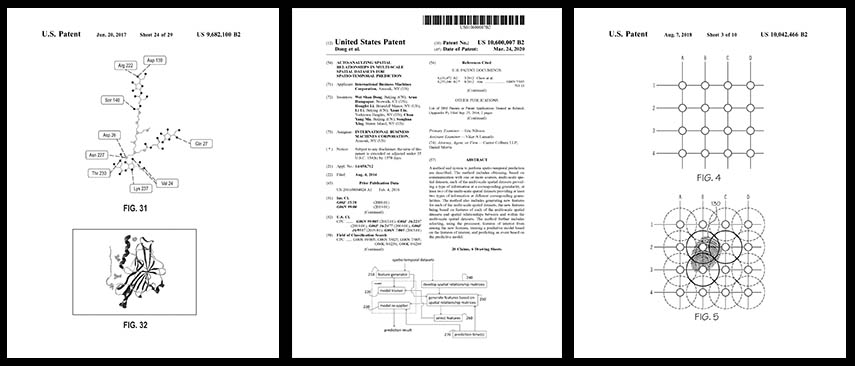

Three IBM patents (left to right) related to macromolecules, epidemic spread algorithms, and touch screens

A Growing Commitment to Open Access

IBM, for one, has been on that road for some time, pushing to share resources and expertise to foster technological progress. It has opened up limited access to its patents before, as with its support of the open source development of Linux software and of environmentally friendly technologies.

The company also recently helped launch the COVID-19 High Performance Computing Consortium, which has made available enormous computing capacity, including some of the world’s fastest supercomputers, to help researchers better understand COVID-19, its treatments and potential cures.

It is all part of IBM’s emphasis on innovation, something that’s reflected in the company’s leading the pack for the past 27 years in obtaining U.S. patents. That includes receiving 9,262 U.S. patents in 2019, the most ever awarded to a single company. Those innovations come in a wide range of areas, whether they derive from a pursuit that’s at the heart of an employee portfolio, an effort to solve a problem of interest to a client, or an idea that comes up over lunch with a colleague.

“Our researchers spend most of their time focused on activities which will enhance IBM’s product set,” said Mark Ringes, vice president and assistant general counsel for intellectual property law at IBM. “But they are also encouraged to explore different areas and to try out new things, and that often develops into patents that are not related to IBM’s traditional businesses.”

Innovators at Work

For James L. Hedrick, a new way to avoid or treat viral infections grew from his research in advanced organic materials at IBM’s Almaden lab in San Jose, Calif. There, he and his team are using artificial intelligence to accelerate the discovery of new therapies to fight viral and bacterial infections as well as cancer. Some of his patented research involves the design of a so-called macromolecule—which is larger than a regular molecule and has specialized components—that could be effective against whole classes of viruses, including the coronavirus.

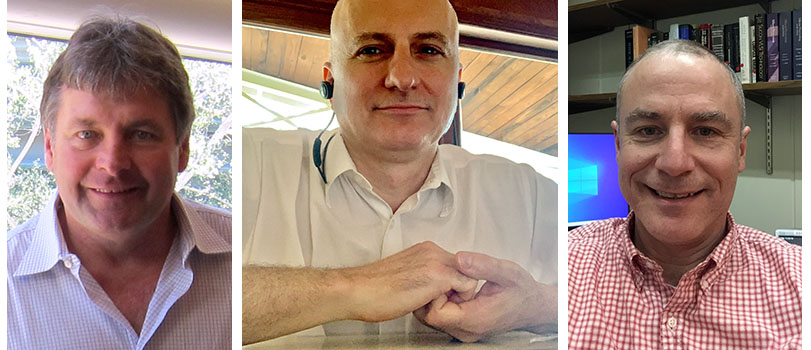

James Hedrick, James Kozloski and Guy Cohen, three IBM researchers whose patents are part of the Open COVID Pledge

The approach stands in contrast to therapies that target the genetic makeup of a pathogen. Because viruses often mutate, such drugs can become ineffective over time. The macromolecule at the heart of Hedrick’s research would target viral proteins and the way the virus interacts with host cells, as the means of preventing or minimizing infection.

“Unlike small molecules that go in there and do very therapeutic, specific interactions,” Hedrick said, “ours are not so specific. They’re, I would say, selective. And in this way we can kind of sidestep all sorts of issues associated with drug resistance.”

Another IBM invention, added to the patent collection this year, involves algorithms that predict the time and geographic range of events, including crime, traffic congestion and the spread of epidemics. Xuan Liu, senior manager for smarter commerce analytics at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., worked with colleagues to design algorithms that can train predictive models.

Safer to the Touch

The impetus for yet another patented innovation that could help stem the spread of infectious diseases was a cafeteria lunch between James R. Kozloski and Guy Cohen at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center.

Cohen, a member of the semiconductor research group, said he noticed people scrolling on their phone screens and using the same hand to put food in their mouths. “I remember thinking, ‘Is that a good thing or not?’” he said. A few months later, the two men had turned that discussion into what Kozloski, the manager of multiscale systems biology and modeling, termed “self-sterilizing pixels.” By adding an ultraviolet LED to the standard red-green-blue array that is in touch-screen devices like cellphones, ATMs and supermarket self-checkout screens, the device would be able to selectively sterilize spots that had been touched—but only when the user wasn’t staring at the screen, to avoid UV damage to the eyes. Their invention might even rearrange screen icons to less frequently touched areas until previous locations could be safely sterilized.

“In a medical setting, touchscreens are invading hospitals, and they have a lot of benefits,” Kozloski said. “But here’s a way to make that safer as well.”

→ IBM stands alone as the global leader in original and applied research. Read more about why IBM puts such emphasis on broad-based basic research, and meet some of our Masters of Invention.

→ Visit the IBM News Room's complete coverage of IBM's response to the coronavirus pandemic